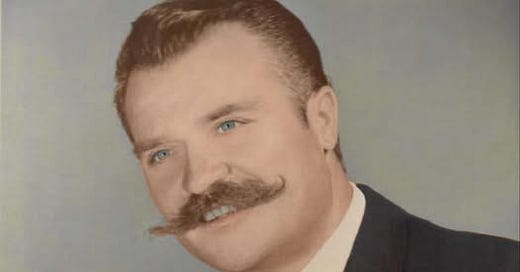

Rinaldo di Lanzo always said he had been stiffed.

Rinaldo was my neighbour.

He died a week or two ago after 95 eventful years and numerous remarkable moments, including a role in a small but significant slice of Perth sporting history.

A native of Casacanditella east of Rome, who joined the Abruzzian diaspora to Perth’s inner-city suburbs in the lean years after World War II, Rinaldo was affable enough though it usually took considerable effort to extract stories from him.

He might had good reason to keep things to himself given his reputation as an after-hours Northbridge regular.

Occasionally, though, he would drop a gem into the conversation before he would head off for his daily trek around Lake Monger or march into Northbridge where he would hold court at his brother’s Sorrento restaurant.

Things like his competitive cycling days in Italy before sailing to Perth at 22 to prepare for the inevitable arrival of his brothers. Three joined him over the years.

Things like pulling spuds in Manjimup, his mandatory first job in WA, or working in gruelling and modestly-paid positions at Wittenoom or Tom Price or the cane fields of Cairns, or the Snowy Mountains scheme.

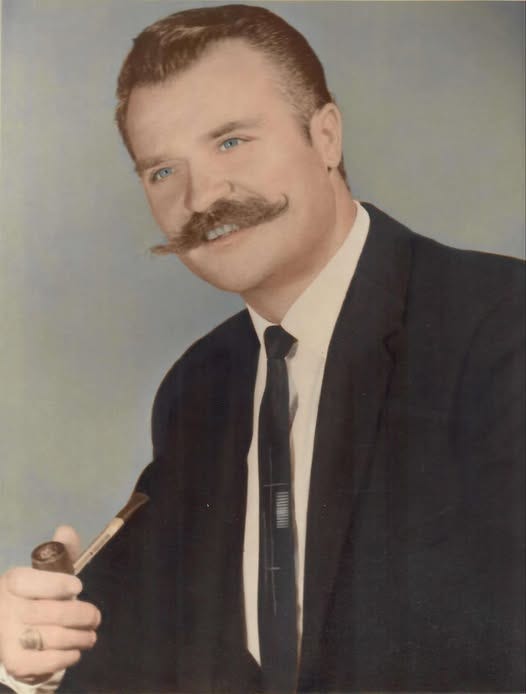

Rinaldo was a strong man with an imposing physique.

Rinaldo di Lanzo cut an unforgettable figure in his younger days.

There was nothing frail about him, nor a skerrick of compromise, even in his 90s when he reverted to speaking only Italian and believed he was once again in his 20s.

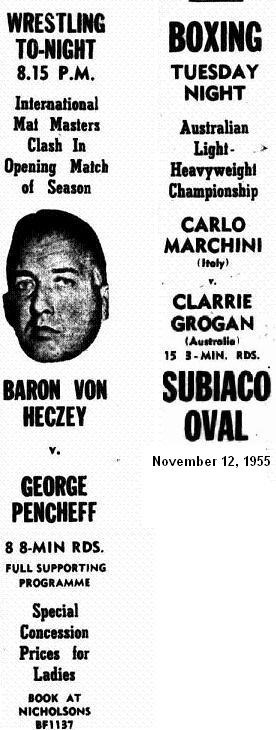

Boxing was one topic that Rinaldo was happy to discuss, though I only discovered by accident, while trawling though old newspapers to flesh out a football project on the history of Subiaco Oval, that he had been a professional boxer at the ground.

Subiaco Oval was a multiple purpose ground that became the headquarters of WA football but, for a period in the 1950s, was also the centre of WA boxing.

A total of 48 professional boxing events were held at Subiaco, mostly in the late 1950s, at a location variously called Subiaco Sports Club or Unity Stadium.

Crowds were decent, with reports of up to a thousand spectators in attendance, with Monday night cards being held regularly in 1958.

Subiaco Oval boxing events were a regular in the 1950s.

Rinaldo was on one of them in June that year as part of the undercard for the WA lightweight title fight in which challenger Mike Dawson upset champion Cyril Bodney.

Subiaco Oval was a five-minute walk from Rinaldo’s house in West Leederville.

It is easy to imagine a man in his prime in his late 20s, someone who had spent most of his life doing hard physical labour and no stranger to forceful confrontations, being attracted to the sport.

His trainer was Randy Jones, the Welsh cruiserweight champion of the 1930s who had moved to Perth to open a boxing gym.

Rinaldo fought Billy Gordon in what would be his sole professional bout, losing on points in a decision that he was adamant was fixed.

“They cheated me out of it,” he told me at least half a century later with a look in his eyes that would have stopped a snarling dog. “I never went back after that.”

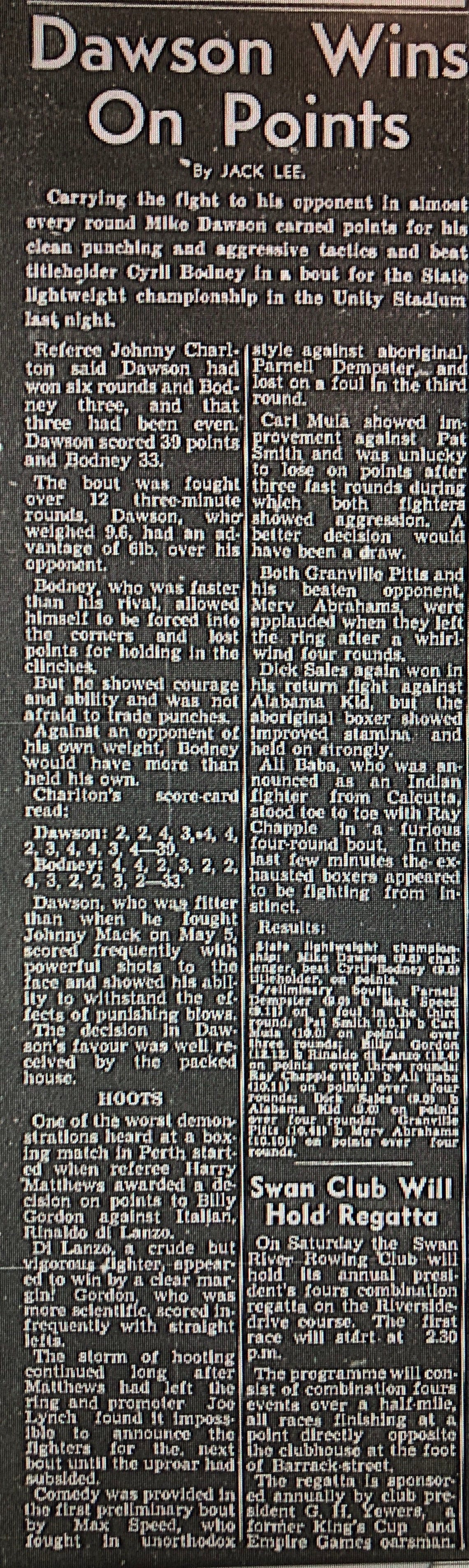

Plenty of beaten boxers have said the same thing but Rinaldo had someone credible on his side – the veteran journalist Jack Lee.

The second of just four permanent chief cricket writers at The West Australian, Jack gave me his scrapbooks when I got the job in 1999.

Lee was also a prominent football and trotting reporter, but turned his typewriter to other sports when required.

Boxing was one of them, with his report on the di Lanzo fight underlining the controversary on the night.

Jack Lee’s report of Rinaldo’s controversial fight.

“One of the worst demonstrations heard at a boxing match in Perth started when referee Harry Matthews awarded a decision on points to Billy Gordon against Italian Rinaldo di Lanzo,” Lee reported.

“Di Lanzo, a crude but vigorous fighter, appeared to win by a clear margin.

“Gordon, who was more scientific, scored infrequently with straight lefts.

“The storm of hooting continued long after Matthews had left the ring and promoter Joe Lynch found it impossible to announce the fighter for the next bout until the uproar had subsided.”

While not enough to prove Rinaldo’s claim that the decision was fixed, the description in the report and the reaction of the crowd explained the vehemence of his stance more than 50 years later.